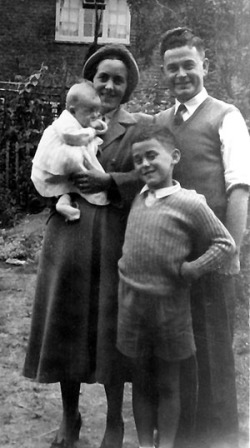

Dr John Nunn - Stars in His Eyes

1955 - I’m the little one.

Have you ever noticed how children often look at the sky, whereas adults rarely do? Certainly my fascination with the sky started at an early age, although initially my interest focussed on the weather rather than the stars. It is said that the English are fascinated by the weather, and it’s true that the changeable English climate, with its frequent and unpredictable variations, provides plenty to talk about. When I was six years old I was already spending a lot of time watching the clouds drifting in the London sky, so for Christmas my parents presented me with a barometer.

I still have the notebook which I kept for several months in 1962, in which I carefully recorded the wind, temperature and barometric pressure every day - climate change researchers may contact me if they wish :)

Given my interest in the sky, it was perhaps only natural that when my older brother David took an interest in astronomy, I followed in his wake. The night sky in London was no better for astronomy then than it is now. These days there is more light pollution, but in the early 1960s the air pollution in London was dreadful. The infamous London smogs often struck in the winter, and when that happened you not only couldn’t see the stars, you couldn’t see the sun either.

Daytime was marked only by a general overall brightening of the environment without any particular source, and when the sun set nothing whatsoever was visible above. The impact of these smogs was so serious that anti-pollution laws were established, which over a period of years dramatically improved the air quality in London. When there was no smog you could see the Moon, the planets and a few stars. However, for the first time in history there was something else to see in the sky - artificial satellites.

These days communication satellites are small, efficient and high up in stationary orbit, so are invisible to the naked eye. Apart from the ISS and the occasional Iridium flare, present-day satellites are unspectacular when viewed from the ground. But back in the early 1960s the Echo 2 satellite, which was just a large metal-coated balloon, was put in a polar orbit and was clearly visible over the whole Earth. This obvious sign of human activity in space caused a lot of people (even adults!) to look at the night sky with a renewed interest and probably stimulated astronomical interest in the Nunn family.

At some point my brother acquired a rather poor-quality 60mm refractor. It was quite pleasant to look at the Pleiades through this modest instrument, but although David claimed to be able to see the Andromeda galaxy with it, I was never able to definitely confirm this. In London, the opportunities for visual astronomy were limited, but once or twice a year my family went camping in the countryside far away from urban light pollution.

Perhaps for some people camping is a pleasant experience, enabling them to appreciate the beauties of nature and so on, but I hated it and the only thing I learnt was how pleasant it is to stay in a comfortable hotel. It also altered my view of history, since hitherto I had felt that the wheel was the most significant human invention, but then I realised that it was actually the flush toilet. So far as I was concerned, the only positive feature of camping was the opportunity to see the night sky in its full glory.

I spent hours lying on my back looking up at the sky, enjoying the Milky Way (which hitherto I had only read about and never actually seen), the moving beacons of the satellites and the occasional flash of a meteor. Round about this time I received a couple of astronomy books as presents and soon became relatively knowledgeable on the subject.

Early chess success

It is said that all good things come to an end, and so it was with my early interest in astronomy. I had shown some talent in mathematics and was also keen on chess, and these two subjects gradually took up more and more of my time.

The difficulties of doing practical astronomy in London and the lack of a suitable telescope also tended to dampen my enthusiasm. However, I continued to follow developments in astronomy with some interest. In the mid 1960s, one of the main mysteries in astronomy concerned the redshift of quasars. If this was due to their great distance then their enormous energy output was hard to explain, but if they were close by then some unknown mechanism must be responsible for the redshift. Now that black holes are known to have a huge energy output, the cosmological origin of quasar redshifts is generally accepted, but at the time the whole subject was hotly debated.

At that time astronomy was going through a kind of revolution and I well remember the excitement when the first pulsar was discovered in 1967, ushering in a whole new branch of the subject. The past half-century has been an exciting age for astronomy, with new developments in all areas, from the use of space probes to further planetary astronomy to the giant telescopes which have probed back almost to the Big Bang itself (and that was another controversial subject in its time).

While all this was happening, my own career was developing. In 1970 I went to Oxford to study mathematics, but central Oxford was no better for astronomy than London. In the vacations, I was playing in as many chess tournaments as possible, which not only improved my chess but also helped fund my university studies.

At any rate it was more fun than traditional student holiday jobs! My big chess breakthrough came at the end of 1974, when I won the European Junior Championship, thereby automatically gaining the title of International Master. After that my chess and mathematics careers continued in parallel, and in 1978 I gained both my doctorate and my Grandmaster title.

I took up a lecturing job at Oxford, but in 1981 I left the academic world to become a professional chess player. This proved a good decision as it gave me more time to study chess, and in the 1980s I achieved several good results, including winning three individual gold medals in the 1984 Chess Olympiad. My peak period was 1989-91, when I was ranked in the world top ten and won a number of top-level tournaments, including two consecutive victories in the famous event at Wijk aan Zee in the Netherlands.

However, it’s difficult to continue playing at the same level indefinitely and in the mid-1990s my life started to change again. Foreseeing the decline of my playing career, I and two friends set up a chess publishing company, Gambit Publications. This company continues to operate today and is recognised as a leading publisher of high-quality chess books.

In 1995 I married Petra Fink, a German chess player, and in 1998 we had a son, Michael. I started to play fewer individual events, preferring instead team chess, and I was part of the successful Lübeck team which won the German chess Bundesliga in 2001, 2002 and 2003. At the end of the 2002/3 Bundesliga season I more or less retired from competitive chess and started to look around for other activities. At one time I had been interested in chess problems and now I decided to take up problem solving, a slightly esoteric branch of chess. This turned out successfully and I have since won the World Chess Problem Solving Championship three times, in 2004, 2007 and 2010, in addition to the European and British solving titles.

Winning Championship in 2010

At the same time I decided to revive my boyhood interest in practical astronomy, which had lain dormant for more than 35 years. I hadn’t looked at amateur telescopes in all that time and I was amazed by what was available. GoTo seemed like magic, and a world away from the small refractor which I had used so many years before.

I bought a Meade EXT-125 and spent a long time in the evenings scanning the sky. I don’t have anywhere to set up a telescope permanently, and in many ways the ETX was an excellent scope since it was light enough to set up easily in the evening, spend an hour or two observing, and then pack away quickly. I no longer lived in London, but the area of Surrey I had moved to is heavily populated and the light pollution remains a major problem.

After a time I became dissatisfied with what I could do with the ETX, so I bought a 10 inch Meade LX200-GPS. The disadvantage of this was that it was too heavy for me to set up on my own, so I required Petra’s help at the beginning and end of each observing session. Fortunately my marriage survived this acquisition, even when I insisted on setting it up at 2 a.m. to observe a grazing occultation of Saturn by the Moon (which was memorable). Thank you, Petra!

After a couple of years I felt that I had looked at everything of interest that could reasonably be seen with the LX200, at least from my location, and I started to wonder about astrophotography.

John, Christian and friend

At the same time I was becoming interested in terrestrial photography and I decided to try attaching my Canon DSLR to the LX200. There was quite a learning curve involved here, and I did manage to take a few pictures of brighter objects, but using the LX200 in AltAz mode wasn’t ideal for astrophotography. The length of time taken to set everything up was awkward and on top of that the light pollution became suddenly much more obvious. My best results with the Meade came when I bought a 400mm telephoto lens and simply bolted the camera and lens to the top of the telescope, which was used solely for tracking. However, only larger objects could be imaged using this method, and the results were still not very impressive.

My astronomical interests took an interesting turn when Frederic Friedel of ChessBase put me in touch with Christian Sasse, who readers will know as one of the motivating forces at GRAS. This was another revelation for me. Suddenly I had access to excellent equipment but, as I soon discovered, there was another learning curve involved. Fortunately, thanks to Christian’s patient help, and the assistance of others at iTelescope such as Pete and Brad.

I soon grasped the concepts involved, and while my skill hardly matches those of astrophotography experts, I was able to produce images which, at any rate, I enjoyed. The person most delighted with this development was of course the long-suffering Petra, who could relax in the evenings. I need not give any examples of these images, as many can be found in the GRAS gallery. Suffice to say that astronomy has given me a great deal of pleasure over the years and has been an important part of my life.

John Nunn